Step outside what you’re doing for a moment. And imagine you can travel through time, watching the long arc of human work unfold like scenes from a silent movie.

You press the button and tumble two centuries back. The air tastes of coal dust and molten iron. Manchester, 1820. Textile mills stretch like cathedrals of smoke, their windows glowing amber in the pre-dawn dark. You’re on the line now, shoulders raw from twelve-hour shifts, lungs scorched by soot. Your hands move in rhythm with the great machines, muscle and sinew trading themselves for coin. The foreman’s watch ticks. Your body is the clock.

You press forward. The scene shifts: 1955. Rows of desks stretch toward fluorescent horizons. It’s the punch-card era. IBM machines hum their electronic lullabies. Efficiency posters hang on concrete walls like corporate scripture. Your name is reduced to a number in a filing cabinet. Your worth is measured by how seamlessly you fit into the chart. Coffee breaks are scheduled. Bathroom visits monitored. You wear the same gray suit as everyone else because conformity is the new productivity.

You jump time again. Glass towers pierce the sky like needles drawing blood from clouds. It’s 2010. Elevators never sleep in buildings that never close. You tap endlessly at blue-lit screens, chasing the dopamine hit of notifications, the hollow high of metrics that spike and crash like fever charts. Late nights with colleagues who unironically call themselves “human resources” over craft beer and kombucha. The city glows. You question your work because deep down you know it’s performance. For algorithms. For visibility. You’re optimizing your LinkedIn presence. Timing your posts. Gaming the attention economy. Doing everything to keep going. The promise was intoxicating: connect everyone, democratize information, turn every person into a creator. But what changed wasn’t just the tools, it was you. You were commodifying your attention.

Now: today. A blinking cursor waits for your prompt. You type. The AI replies faster than thought, cleaner than anything you could’ve ever written. The words are polished. Efficient. But there are no fingerprints on them. No trace of the struggle.

You’re prompting now and translating human intent into data cues for the algorithm. The AI reflects back at you with such clarity of information, that you wonder: “how can I compete with it”? You feel something is off. The world is more fragile than before. The institutions that once held the promise together now echo hollow. We scroll through crisis. Work becomes both everything and nothing.

When we step back through time, a pattern emerges: every era promises to elevate human potential at work, yet each one finds new ways to measure us and box us in.

But AI rewrites the script. It calibrates every metric at once, accelerating us into optimization’s endgame: a system so efficient, it no longer needs the people it was built to serve.

Only then do we begin to see the truth: we’ve been measuring human value at work all wrong.

Let’s look closer.

The Death of Craft (A Very Brief History)

How we hollowed out human value for the wrong metric

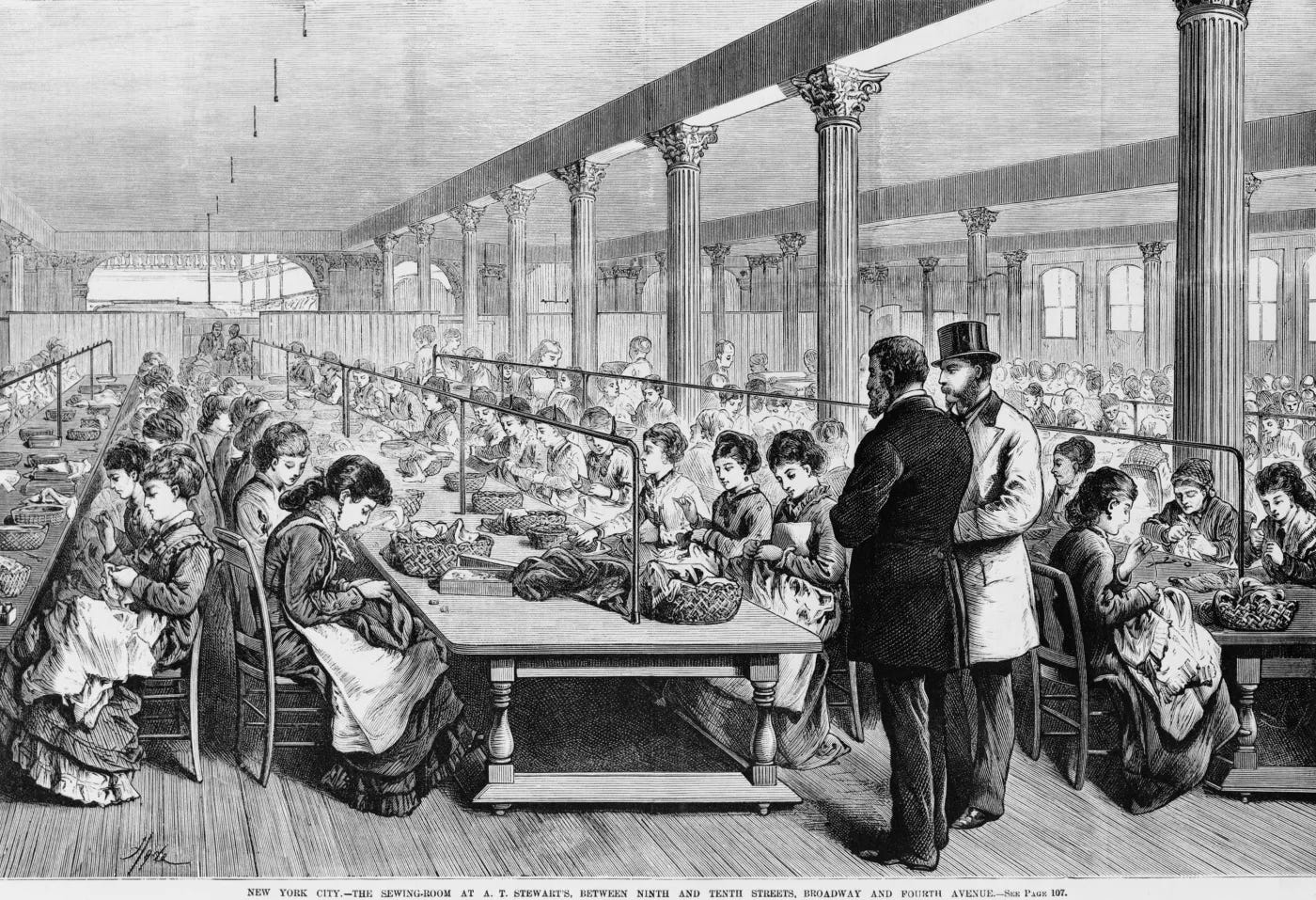

Before the industrial revolution, to work was to know something deeply. The blacksmith understood his iron as if it had a temperament. He could sense when the metal was ready by the sound it made under his hammer. The weaver felt the rhythm of each thread, how it pulled against her fingers depending on the season or moisture in the air. These weren’t just skills, they were relationships. Passed down, refined, embodied.

Craftsmanship meant control over both process and product. The same hands conceived and shaped. There was no separation between the idea and its execution, no divide between thinking and doing. Tools were extensions of the body, not barriers to it. Time moved differently though. Output was slower, but not lesser. What mattered was the quality of attention, not the speed of production.

Then came the machines and with them, a new philosophy of human value.

Work became a System

In the early 20th century, Frederick Taylor stood on factory floors with a stopwatch in hand. He wasn’t interested in what work meant. He wanted to know how fast it could be done. In The Principles of Scientific Management (1911), Taylor laid out his vision: break every task into its smallest parts, eliminate variation, and reassemble work as a system that operated with mechanical precision.

A worker wasn’t a maker anymore. He was a moving part. And like any part, his value could be measured in units per hour. Shoveling coal, lifting steel, tightening bolts … every gesture was timed, priced, standardized.

Craftsmanship didn’t disappear overnight. But it simply became inefficient in the new system. Too slow. Too idiosyncratic. Too human. The new system didn’t care for wisdom passed down or intuition honed by years of trial and error. It cared for consistency. And so the first trade was made: embodied knowledge for mechanical efficiency. Muscle for survival.

What died wasn’t just a way of making things. It was a way of knowing … a way of being in the world.

From Machines to Management

As machines scaled, so did we.

By the mid-20th century, the factory evolved into the office. The tools changed: typewriters, filing systems, corporate ladders, but the logic kind of stayed the same. Now, instead of timing shovels, we tracked performance reviews, KPIs, and managerial hierarchies. The worker became a “human resource.” An input to be optimized within a system too complex for any one person to understand.

The office was supposed to be a promotion. It looked cleaner. It paid better. But the metrics only grew more abstract. Success was defined not by the quality of your ideas, but by your ability to operate smoothly within bureaucratic machinery. Reliability replaced originality. Conformity became a feature of this era.

To be clear: each phase brought material comfort. Life got easier … with big salaries, benefits, stability. But in the quiet corners, beneath the surface, something felt hollow to us. We traded our own judgment for protocol. We gave up discretion for process. And the more we scaled, the more we forgot what it meant to work with our whole selves.

Performance as Identity

Then came the platforms.

By the early 2000s, work no longer stopped when you left the office. It followed you home, lived in your pocket, monitored your steps, your clicks, your time online. The internet rewired work into performance. Social media turned identity into a stream of content. We were no longer making objects. We were curating ourselves.

The metrics multiplied: likes, shares, impressions, conversion funnels. What counted now was visibility. Influence. Reach. A new working class was born: the creator. Every person, a personal brand. Every gesture, content. Every moment, data.

We weren’t creating for each other, we were creating for the algorithm. Some mastered the performance: “like four posts”, “leave comments on big accounts”, “follow the playbook” …

Once again, the tools rewarded a new kind of optimization: time traded for dopamine, authenticity for engagement, presence for performance. Attention became the product and we learned to manufacture it.

Strangely, in an age of constant visibility, we became less seen. We didn’t just build tools to optimize, we began optimizing ourselves. Peter Thiel put it bluntly in a recent interview: “Without AI, there’s just nothing going on.” He argues that while AI offers real progress, it largely acts as a stopgap in an era otherwise marked by stagnation. And he’s right. By this point, startups weren’t solving real problems, they were solving for pitch decks.

Everyone cracked the same playbook: repeat what worked, raise fast, scale faster. Optimization became a game people could play without thinking. Just follow the steps, feed the funnel, watch the metrics move.

The result? A sea of lookalike apps, thousands of interchangeable fintech tools, and endless “Uber for X” clones. This wasn’t a failure of innovation. It was a failure of imagination, and it started long ago.

The Final Optimization: AI

What we’re living through isn’t just another wave of disruption. It’s something deeper, an acceleration so total that it collapses every previous framework of human value at once.

Economists call it a “supply shock”, a sudden change in the cost or availability of production inputs that reshapes entire systems. In the past, these were physical: steam, electricity, the internet. But this one is ontological.

For the first time in two centuries, we’ve created a system that can optimize for all previous metrics of human value (faster and cheaper). AI can process more information than any digital native, coordinate more efficiently than any middle manager, and execute tasks with more consistency than any Taylorized worker. It synthesizes knowledge, generates content, automates judgment. It simulates everything we spent generations being trained to do.

In other words, the system has learned to measure itself. And once that happens, the human begins to exit the loop. And this is the breaking point of what we’re experiencing right now. The moment we realize the optimization wasn’t leading to liberation. It was just leading to erasure.

Not because AI is inherently good or bad. It didn’t break the world, it revealed what was already broken. It exposed how our definition of work, and our measure of human value, were built on a brittle foundation.

Now we’re living in the aftershock. The fear isn’t just about being replaced, it’s about becoming irrelevant to the very systems we spent centuries building.

The most urgent ethical question of our time might be this: “If AI cures disease, launches us to new planets, and reinvents every system we know, is it still worth it if, in the process, it leaves us in shackles?”

That question was recently posed, indirectly to Peter Thiel. In an interview, columnist Ross Douthat asked him:

“You would prefer the human race to endure, right?”

Thiel paused.

He didn’t answer right away.

“You’re hesitating,” Douthat observed.

The silence said more than any theory could. Not because Thiel didn’t have an answer, but because he might already know it. And it’s possible he found it strange to say it out loud.

The Human Metric

“The difference between the right word and the almost‑right word is the difference between lightning and a lightning bug” - Mark Twain

I love this quote because it captures exactly what’s at stake right now. Tech pundits still frame AI as a binary choice: mindless acceleration toward total automation, or a nostalgic retreat to candle-lit hand tools. But neither story reflects the data or our historical experience.

Twain’s quote isn’t just about writing, it’s about the human instinct to care about getting it right. To know, in your gut, the difference between good enough and excellence. That difference shows up in the work of a nurse who notices the subtle sign of distress or an engineer who keeps iterating until something magical really works.

We’re standing at a real inflection point. AI can now write code, diagnose disease, compose music. It’s already being used by millions, justifying layoffs, reshaping industries. And yet, oddly, many are still debating whether it’s “smart enough” when we should have been debating “what makes us whole again?”

Because here’s something simple and enduring about humans: we care.

I’ve worked with people across disciplines, civil society leaders, NGO workers, designers, artists, caregivers, engineers, and again and again, I see it. People care deeply about their contributions. Whether it’s tending to the elderly or designing a combustion engine, that care is real.

But we forgot this. We forgot because, time and time again, the system didn’t reward our presence. It didn’t value our judgement. It only rewarded output at scale. And in the process, we sidelined the quiet dignity of those who show up every day and care, who make things work not just with tools, but with judgment, patience, and pride.

Toward a New Measure

So here we are, time travelers and students of technology asking the question: How did we get here?

But to me, the one I can’t stop thinking about, is: Where do we go next?

We played the optimization game. We built the systems, hit the metrics, scaled the outputs. And for what it’s worth, we got really good at it. But maybe, just maybe, it’s time to measure our contributions differently. Not by speed or scale, but by a new kind of human metric that puts care and craft back at the center of work.

In a post-AI world, we can’t compete on speed and scale. And we shouldn’t. That was never our greatest value to begin with. It was necessary for a time, but it was never the best use of our capabilities. Speed still matters. But speed without discernment is just noise. And we’re already seeing the consequences. AI has flooded the internet with bloat: SEO-stuffed blog posts no one reads, generic LinkedIn thought leadership, AI-written books that sell in bulk but say nothing.

So what does a human metric in the post AI world mean? Well … it means shifting what we value and therefore what we measure. For decades, we’ve measured work by how fast it’s done, how far it scales, how efficiently it performs. But those metrics were built for machines, not people.

A human metric asks different questions:

Did this task require discernment?

Was care present in the outcome?

Did this reflect judgment, not just automated logic?

Did it leave the world more coherent, more meaningful, more beautiful?

We’re not measuring output, we’re measuring integrity. Not just what we produce, but how we show up to make it.

Why does this matter? Because in a post-AI world, machines will do most things faster and cheaper than us. Our value will come from the things they can’t do well: context, interpretation, ethical choice, emotional texture, taste.

The human metric becomes the signal that work is still worth something, not because it’s nostalgic, but because it shows presence, care, and excellence. In a noisy, automated world, the human metric says:

This was made by someone who gave a damn

This metric isn’t some luxury or soft, feel-good idea. It’s not optional, and it’s not something we can tack on later. It’s defined by three deeply human capacities (judgment, presence, and care) each essential in a world increasingly run by machines:

1. Judgment: Discernment under uncertainty.

The ability to choose what matters from a sea of options.

Example: When GitHub Copilot suggests 20 code snippets, the skilled engineer doesn’t just pick what works, they pick what lasts.

2. Presence: Attention in context.

The capacity to notice what sensors miss.

Example: The nurse who sees pain behind a calm face. The teacher who senses confusion before it’s spoken.

3. Care: A commitment to meaning.

The refusal to ship mediocrity just because the model says “good enough.”

This isn’t perfectionism, it’s integrity. A human insistence on excellence. And excellence isn’t a virtue reserved for the laptop class. It belongs to anyone who takes pride in what they do. As a society, we’ve undervalued that kind of care for too long because we lacked a metric to see it.

These aren’t abstract ideals. Even by traditional quality metrics, they’re already reshaping how we work. They are proving to be the difference between generic output and work that truly resonates.

At Johns Hopkins, robotic arms now handle precise cuts, while senior surgeons make real-time decisions. The result? 23% faster operations, 31% fewer complications. Surgeons became more essential, not less. In Chile’s education pilot, AI tutors handled drills and grading. Teachers doubled their one-on-one time. Students didn’t just learn faster, they developed better critical thinking and emotional connection. In manufacturing, textile artisans use AI to simulate patterns for testing and experiments without losing their creative edge.

AI can scale the infrastructure, but only a human metric can elevate the experience and create meaning within that system.

Our value in the post-AI world isn’t in resisting the tools or blindly serving them. It’s in using them to reimagine how we learn, how we care, how we build, and how we belong. What this new human metric looks like, and how we apply it, won’t be simple.

There will be tension and trade-offs. We can’t afford to romanticize human input, nor ignore what machines now do well. But we must begin the dialogue now before the systems calcify around the wrong values again.

Over the next few weeks, I’ll lay the foundation for what this new metric could mean and how it can show up in the real world. To the peers and friends who shared your visions with me: thank you.

This project is for you and for anyone who still believes that progress should feel human. That excellence should have soul. And that the future is still ours to shape.

This captures something I’ve been trying to name in my own work: the difference between optimizing for output and designing for meaning. The way you trace the arc from craft to compliance to performance is felt. Especially now, when so many of us are navigating systems that move faster than care.

What you’re offering is a reminder that judgment, presence, and care aren’t luxuries. They’re the baseline for anything worth building next.

Thank you. I'm trying to teach systems to reflect this level of humanity.

Your description of the connection from the technology industrial revolution to AI is beautiful. It illuminated something I'd felt but not articulated.

I've got an alternative theory about Craft...

It's not that Craft is dying, instead we're losing Art. If you look at a streetlamp from 100 years ago, the beauty was in its Art. Why did they invest that time and effort making a functional object so gorgeous? Because...?

Craft is focused on "HOW?" - the function of the output. This is the realm of automation as progressively AI takes on more and more of the "how-ing".

Art is focused on "WHY?" and "WHAT?" The purpose of the output and what could deliver this purpose. At this point, an AI has no reason to do anything, so it can't decide what to make, what is good without a human.

But any human can use AI to augment and expand what's possible - and automate what stops them creating the previously impossible.