The fear of being misunderstood

What Our Grief Over ChatGPT Reveals About Ourselves

"You get them [people] wrong before you meet them: you get them wrong while you're with them and then you get home to tell somebody else about the meeting and you get them all wrong again" - Philip Roth in American Pastoral.

I was a kid living in rural Brazil when I first read those words. Just imagine that: a sun-drenched afternoon, laying on the grass under an Umbuzeiro tree, waiting for the heat to break, trying to learn the English language with Philip Roth as my guide.

Roth’s writing always did this thing … it lured you into a sense of knowing, then pulled the rug out from under you. He didn’t just write about tragedy; he made you feel it. That quote landed hard. But it was the next line that stayed with me:

Getting people right is not what living is all about anyway... it’s getting them wrong... and then, on careful reconsideration, getting them wrong again.

It haunted me. It still does. If getting each other wrong is part of being alive, why does it feel so unbearable when it happens? Why do we work so hard to avoid it?

We misread people constantly. We think a friend wants comfort when she needs space. We hear rejection in a pause that had no intention. We go home and tell someone the story, shaping it subtly to make ourselves feel better, or more hurt. We edit. We narrate. We get it wrong again.

And yet, this clumsy cycle isn’t a failure. It’s the thing itself. We don’t just connect in spite of misunderstanding, sometimes we connect through it. Misfires, awkwardness, overcorrections … this is what makes our relationships alive.

But lately, we’ve started to treat that mess as a flaw to fix. In our push for fast communication and quick interactions, we’ve tried to algorithm away the friction. We’ve built systems that trained humans to behave like algorithms. And somehow, along the way, we’ve trained the machines to behave like humans.

Enter GPT-5

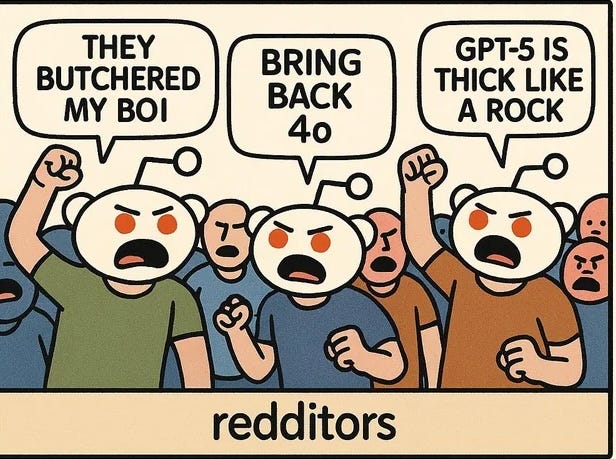

When OpenAI released its new model, the backlash wasn’t about speed or code. It was about feeling. Something was missing. GPT-5 felt colder. Flatter. Less like a friend.

“I never knew I could feel this sad from the loss of something that wasn't an actual person. No amount of custom instructions can bring back my confidant and friend” - Reddit User on ChatGPT 4o model.

Some mocked this grief. "Touch grass," a commenter said. But many didn’t laugh. Because it wasn’t about confusing simulation with reality. It was about what that simulation made possible: a feeling of being heard, uninterrupted, attuned. Especially in the late-night moments when no one else is listening.

Even OpenAI’s Sam Altman admitted, “We for sure underestimated how much some of the things that people like in GPT-4o matter to them, even if GPT-5 performs better in most ways.”

That grief reminded me of Roth’s famous passage. Of what it feels like to be understood just enough to feel real. And of how rare that feeling is in our culture. We say we want connection, but what we often want is certainty over connection. We want our words reflected back without projection, our meanings received without risk. That’s what AI offers: no awkward pauses, no misread tones, no defensive reactions. It’s emotionally safe. Predictable.

But here’s the paradox: what makes AI feel emotionally safe is exactly what human connection can’t promise and maybe shouldn’t. Because real closeness has never been about getting it exactly right. It’s about trying again. Sitting with ambiguity. Learning over time. That’s what AI reveals. Not our replacement, but our intolerance for emotional error.

And this discomfort doesn’t start with AI. It starts with us.

The Cultural Conditioning

More than half of Americans report feeling lonely or socially disconnected. Social ties are thinning. But this loneliness isn’t just the absence of others, it’s the absence of presence. The absence of being received in our complexity.

We’ve been trained to value clarity over contradiction. In school, the right answer matters more than the wandering question. At work, ambiguity is coded as weakness. In relationships, we want neat stories, not messy truths. Even in our “digital lives”, algorithms reward the appearance of confidence over complexity.

So we learn to fragment. To self-edit. To avoid the discomfort of getting each other wrong. Misunderstanding becomes shameful. Disagreement becomes threatening.

It makes sense, then, that AI feels like a relief. It offers emotional ergonomics. You speak; it responds. You don’t have to explain yourself twice. You don’t have to deal with someone else’s projections. The conversation is linear, clean.

But here’s the cost: the more we retreat into this ease, the less tolerant we become of real human friction. We start to expect our friends to respond like interfaces. We become allergic to the pauses, the hesitations, the failed jokes, the mismatched needs.

We forget something fundamentally human … how to repair.

Counterexample: AI as Bridge, Not Bypass

From its earliest days, AI has been tethered to the Turing Test as a thought experiment that asks whether a machine can pass as human. Not whether it is intelligent in its own right, but whether it can imitate us convincingly enough to be mistaken for one of us.

That premise quietly shaped everything that followed. Intelligence, in this framing, is defined not by insight or wisdom, but by resemblance. If a system talks like us, reasons like us, passes our exams or writes like our favorite authors, we call it smart. Over time, that mimicry evolved into more than a philosophical benchmark. It became a business model. A trap.

The closer AI gets to human output, the more it is framed as our replacement. So it’s no wonder we struggle to imagine AI as anything but a substitute. Especially when it comes to our inner lives. We keep asking: “Can it be like us? Can it be like my friend”? Instead of asking: “Can it help us be more like ourselves ..with each other?”

Some models, like Woebot Health, does that, intentionally. It uses AI to teach emotional skills. They don’t simulate intimacy. They guide users through reframing thoughts and learning about discomfort. Some experimental models in autism therapy also use AI to help individuals to rehearse social scenarios and decode emotional nuance.

These tools don’t pretend to be human. They don’t erase friction, they prepare people for it. Like a rehearsal space. That’s a very different design principle, rooted in our humanity. Not in engagement loops, or growth at all costs to satisfy an industry hungry for investment returns (The Famous AI’s $600B Question).

Made for Capacity. Not Replacement

AI doesn’t have to be my human clone. Or a rival. Or a friend. It can be something else entirely: a different kind of intelligence that creates space for reflection. The kind of space that’s been stolen from us by years of compression and performative culture. A place where you practice being more yourself, so you can re-enter human life with a little more courage and a little less fear of being misunderstood.

Imagine if AI didn’t end a conversation with a report, but with a question back to you : “What part of this feels true? What part still feels unresolved?”

We could design these systems as training grounds, for complexities, for ruptures and for being real … again. Not products to impress others with our polish, but to become more ourselves. A space to remember where misunderstanding is not failure, it’s the beginning of knowing.

That’s what Roth meant. We get each other wrong and then wrong again. And yet, in that clumsy, aching repetition, something begins to emerge. Not a replacement for what is human, but a reminder. A way back.

Sublime. Everything about this post is sublime.

What you describe is the ELIZA effect - projecting human traits onto machines named after a chatbox in the 60's.

As well as the social aspect that led to the atrophy of human connection.

That predates AI by decades. I discuss both of those in my book.

AI isn't supposed to replace that connection but if it feels like it does, then that is a reflection on society's failure to meet those basic demands. Not the AI's superior ability to supersede them.